Most experienced eclipse chasers recommend that first-timers — especially those attending their first total solar eclipse — just watch the spectacle and not try to capture it in images or video. There's so much to see with your eyes, and you'll be able to view countless other people's pictures and movies online afterward anyway. But now that so many people carry smartphones with built-in cameras almost everywhere they go, it's inevitable that most first-time eclipse-watchers will want to record something of their experience for later viewing. On this page we provide the essential information every eclipse photographer needs to get the best possible results.

When shooting still images or video of a solar eclipse, one rule is paramount: special-purpose solar filters must always remain on cameras and telescopes during the partial phases (including the annular phase of an annular eclipse). Only during totality is it safe to remove them (see our Eye Safety section). Filters should fit snugly over the front of all camera lenses and telescopes, but not so tightly that they’re difficult to remove quickly at the start of totality.

Here are four things to keep in mind while reading this article:

- The suggestions offered here are intended mainly for users of digital single-lens reflex and mirrorless cameras (DSLRs and DSLMs); we also offer some tips on shooting with smartphone cameras. Some of the comments on this page won’t apply if you’re shooting with film or recording on tape.

- Comments about shooting annularity or totality apply only if you’re within the path of the Moon's antumbra (for an annular eclipse) or the path of the Moon’s umbra (for a total eclipse). On October 14, 2023, the path of annularity is only about 125 miles wide but stretches from Oregon to Texas to parts of Central and northern South America. On April 8, 2024, the path of totality is only about 115 miles wide but stretches from Mexico to Texas to Maine to eastern Canada. Outside either path, you’ll have only a partial eclipse.

- This article doesn’t specifically address taking eclipse photos through a telescope, though some of the tips concerning telephoto lenses apply equally to telescopes; see the links at the end if you plan to shoot through a telescope, which is really not something you should try unless you have prior experience.

- You should practice before the October 14, 2023, annular eclipse and the April 8, 2024, total eclipse by shooting the uneclipsed Sun (with solar filters over the front of your optics, of course) in the days or weeks leading up to the eclipse.

Size Matters

If you simply want to shoot scenics and don’t care about eclipse close-ups, then a smartphone or point-and-shoot camera will suffice. If it has a decent zoom lens, some manual control, and perhaps image stabilization, you can take snapshots that record the progress of the partial phases (and the annular phase of an annular eclipse) through a solar filter, landscape scenes showing the dropping light level during the final minutes before totality, the 360° horizon glow visible during totality, and even totality itself. (Of course, those last three subjects don't apply during an annular solar eclipse, but if you set the ISO, shutter speed, and f-stop so they don't change during the 10 minutes or so before/after annularity, your landscape shots will capture the dropping/rising light level.)

Before pointing your camera at the Sun at any time other than during totality, remember to put a special-purpose solar filter over the camera lens (and over the viewfinder if the camera lacks through-the-lens viewing).

Several new products are available to facilitate shooting solar eclipses with smartphone cameras; see the "Solar Filters for Smartphones" section of our Suppliers of Safe Solar Filters & Viewers page.

For close-up images of the eclipsed Sun, you’ll need a digital single-lens-reflex (DSLR) or mirrorless (DSLM) interchangeable-lens camera with a telephoto lens, or a point-and-shoot camera with a high-power zoom lens.

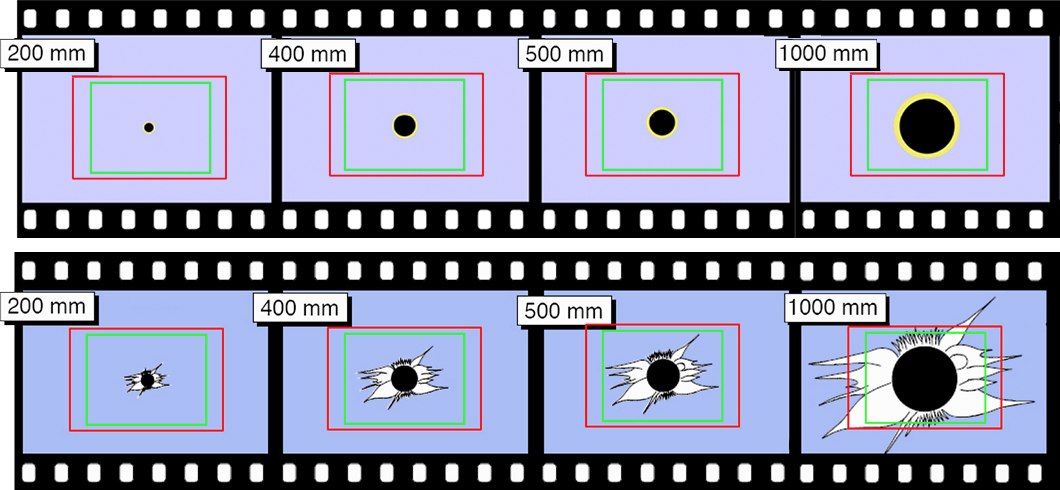

A normal (50-mm) or wide-angle (35-mm to 10-mm fisheye) lens will take in the overall scene but will not capture coronal detail during totality or show the "ring of fire" clearly during annularity, because the eclipsed Sun’s image will be tiny. To get a moderately large solar image, you need a lens with a focal length of at least 300 mm. (All focal lengths in this article are 35-mm equivalents; if you’re not sure how to convert your lens’s focal length to its 35-mm equivalent, check your owner’s manual or the manufacturer’s website.) For close-ups of Baily’s Beads during an annular or total solar eclipse, and of the diamond rings, the chromosphere, prominences, and the corona during a total solar eclipse, a 1,000-mm telephoto (or longer) is recommended. That’s the realm of telescopes; again, we don’t cover that kind of imaging here, as it’s recommended only for those with experience.

Software developer Xavier Jubier has posted his Shutter Speed Calculator for Solar Eclipses online. Among other features, it illustrates the image size of the Sun for various combinations of camera model, sensor size, and focal length.

Exposure Counts

While you’re practicing shooting the Sun to see how much of your camera’s frame it will fill, try testing for exposure too.

The requirements for annular and total solar eclipses are different. During an annular eclipse, the Sun remains intensely bright from start to finish, so one exposure setting will suffice (except as noted below). During a total eclipse, the Sun's brightness changes by orders of magnitude between the partial phases (when you'll shoot through a solar filter) and totality (when you'll shoot without a filter). Moreover, the brightness of the solar corona varies enormously with radial distance from the Sun. So while one exposure may work for the partial phases, you'll need a wide range of different exposures to capture all the phenomena of totality.

During the transitions between the the partial phases and totality at second and third contact, the scene in the sky changes rapidly. You'll already be worried about getting your solar filter off and back on at the right moments, so you don't also want to worry about changing your ISO, aperture (f-stop), and exposure times. It's better to use one ISO and f-stop throughout the entire eclipse and vary only the shutter speed.

On a sunny day well in advance of an annular eclipse, place your camera in manual mode, set the ISO to 100 or 200, set the aperture to f/8, attach your solar filter to the lens, shoot a range of different short exposures of the Sun (likely in the range of 1/500 to 1/4000 second, and see which image turns out best. Then take another shot or two with the camera set on auto to see how the results compare with the images acquired in manual mode.

On the day of the annular eclipse, use the setting that produced the most pleasing results during your tests. If your camera supports bracketing — automatically shooting the exposure time you've dialed in as well as one a bit longer and one a bit shorter — you should enable that feature to compensate for minor variations in sky conditions and, where applicable, the Sun's changing altitude in the sky.

When testing your exposure settings for a total solar eclipse, try higher ISO numbers and larger apertures (smaller f/numbers) than mentioned above for an annular eclipse, because totality is much fainter. Late-model digital cameras often show no noise until the ISO is set above 400; point-and-shoot models generally aren’t as good. Experiment with ISO settings of 400, 800, and perhaps even 1600 to figure out which setting produces the best images of the full Sun when combined with apertures of f/5.6 or f/4 and the shortest exposure times your camera can deliver. On eclipse day, you'll use your fastest shutter speeds during the partial phases and a wide range of shutter speeds during totality.

The Sun's surface brightness remains constant throughout most of the partial phases of the eclipse, so no exposure compensation is necessary. During the thin-crescent phases shortly before and after annularity or totality, and during the annular phase of an annular eclipse, you might want to increase the exposure time by a factor of 1.5 or even 2 (equivalent to one f-stop), since the solar limb (edge) is noticeably fainter than the center of the disk. If haze or clouds interfere on eclipse day, you may need to bracket by a full f-stop or more (or switch to automatic mode) to get decent results.

To capture the faint outer corona during a total solar eclipse, you'll want to push your exposures as long as possible. The maximum practical exposure depends on whether your camera is hand held (and if so, whether it has image stabilization), attached to a fixed tripod, or tracking the sky on a motorized mount to compensate for Earth's rotation.

On eclipse day, make sure you preset your ISO rating and f-stop; don’t let your camera (via its “auto ISO” function) do it for you. For any combination of f-stop, ISO numberxxc , altitude of the Sun in the sky, and elevation of the observer above sea level, Xavier Jubier's Shutter Speed Calculator for Solar Eclipses suggests an exposure time for each phase of the eclipse. Fred "Mr. Eclipse" Espenak's Solar Eclipse Exposure Guide does the same in a simple tabular format. Don't rely exclusively on tools like these — use them as a starting point. As noted above, test your setup on the uneclipsed Sun well in advance, and on eclipse day, bracket your exposures.

Photographing totality is a different matter altogether and is something you can’t practice beforehand (though you can shoot the full Moon as a brightness test, because it’s about as bright as the Sun’s inner corona). For specific suggestions on this topic, see “Shooting Totality” below.

Focus Is Critical

Don’t leave the job of focusing to your camera’s autofocus system. Manual focus is the way to go, and most telephoto lenses provide this option. As soon as you’re set up at your eclipse-viewing location, attach the solar filter to the camera’s lens, aim at the Sun, and focus. When sunspots are visible, as is likely to be the case in 2023 and 2024 since the Sun is near "solar maximum" (its cyclical peak of magnetic activity), focus on the spots; otherwise, focus on the solar limb. Take a couple of test shots to ensure that the images look sharp.

Once the lens is focused, secure it by sticking a strip of masking tape to the lens’s focus ring. If you’re using a zoom lens, lock it to your preferred focal length with tape as well, since it can “self adjust” without warning — particularly if the lens is pointed high in the sky. For a total eclipse, make sure your solar filter can be easily removed when totality begins, and restored when totality ends, without affecting the focus or the zoom.

Keep It Steady

Even though you’ll likely be shooting the partial phases of any solar eclipse and the annular phase of an annular eclipse at reasonably fast shutter speeds, there’s nothing like a solid tripod to keep your optical system steady. This is especially true for a total solar eclipse, when you'll be shooting longer exposures during totality. The tripod is particularly important if you’re using a camera with a long-focal-length telephoto lens, which may be heavy and unwieldy.

Many cameras or the lenses that attach to them incorporate image-stabilization (IS) systems. They’re useful for normal or wide-angle photography, but image stabilization can help only so much when shooting the eclipsed Sun with a telephoto lens. The combination of IS and a tripod will ensure that your images are as sharp as possible (but see the next paragraph). Two very helpful things that image stabilization will do is let you use a lighter-weight tripod than you might otherwise and help reduce vibrations caused by a breeze.

Some image-stabilization systems get confused when a camera is mounted on a tripod, causing the image to jerk around. As we keep repeating, test your equipment before eclipse day to make sure you know which features improve your results, which features are best avoided, and how to enable the former and disable the latter.

Shooting Annularity

Obviously this section applies only if you're in the path of annularity for an annular solar eclipse. (Skip ahead for tips on shooting totality during a total solar eclipse.) To find out whether your home or any other specific location lies within this path on October 14, 2023, see Xavier Jubier's Google Map, which supports zooming in to street level.

In 2023, annularity lasts nearly 5 minutes. That’s plenty of time for photography, because unlike during totality, there are not a lot of visual distractions in the sky — no diamond rings, no corona, and no 360° sunset glow on the horizon. Annularity is what you’ve come to see and record. Other than acquiring a nice set of partial phases of the gradually shrinking Sun, the three events you’ll probably want to concentrate on are second-contact Baily’s Beads, annularity itself, and third-contact Baily’s Beads. Make sure your solar filters remain on all your camera gear throughout the entire eclipse.

Shooting Baily’s Beads is a little different than shooting annularity itself. If you want to capture a bead sequence, then a few minutes before the onset of annularity, decide on your shutter speed based on your latest photos of the diminishing crescent. Start shooting just before second contact — either manually or via a continuous shooting function — and keep firing until the Moon is fully silhouetted on the Sun. Do the same thing just before the start of third contact, continuing until the Sun is again a thin crescent.

During annularity, you have plenty of time for a variety of imaging. Shoot people, scenics, the Sun at mideclipse (when the Moon is centered on the solar disk), or the rings of sunlight on the ground beneath any leafy trees.

Shooting Totality

Obviously this section applies only if you're in the path of totality for a total solar eclipse. To find out whether your home or any other specific location lies within this path on April 8, 2024, see Xavier Jubier's Google Map, which supports zooming in to street level. If you don't already live or work within the path of totality, we strongly recommend that you travel there if you can, especially if you've never experienced totality before (and because the next total solar eclipse to sweep across North America doesn't occur until 2045). As described elsewhere on this site, the difference between a total solar eclipse and a partial or annular eclipse is quite literally the difference between night and day! (See our 2-minute video explainer if you're still unsure whether to make the effort to get into the path of totality.)

While the total phase of a solar eclipse always seems to pass quickly, there are sights and events within totality whose passage is even more fleeting. The diamond ring fades (or brightens) within seconds, and the red chromosphere and prominences usually aren’t visible for much longer. The challenge of imaging totality is capturing these sights during their brief appearance. Fortunately, the corona is visible throughout totality, and just about any exposure will record some part of the Sun’s pearly outer atmosphere.

But you won’t get any pictures of the total phase if you don’t remove the solar filter from your camera at the beginning of totality! If you forget, all you’ll record is blackness.

Rapid changes occur during second and third contacts, the beginning and end of totality, respectively. At these times, you don’t want to be fumbling with your camera’s settings. Instead, decide in advance on the ISO/f-stop/shutter-speed combination you want for both contacts and set your camera accordingly before the onset of each diamond ring. Even better, as noted above, use the same ISO and f-stop settings throughout the eclipse so that you need only vary the shutter speed to capture different phenomena.

The Sun’s atmosphere varies tremendously in brightness. The inner corona shines as bright as the full Moon; the outer corona is less than 100th as bright (in other words, it’s quite dim). One exposure cannot capture this wide dynamic range. That’s why eclipse photographers shoot a sequence of exposures (using a fixed ISO and f-stop) that range from very short ones to very long ones. This gives you the best chance of capturing all aspects of the magnificent solar corona.

At the short end (1/1,000 second or less), only the innermost corona clinging to the solar limb appears. At the long end (1/10 second or longer if you can hold sufficiently steady), the inner corona is burned out, but the faint tendrils of the outer corona show up nicely. There is no single correct exposure for totality, so your best bet, at any f-stop, is to shoot a sequence spanning the full range from the short exposure you used for the partial phases to the longest exposure you can manage without blurring (perhaps a few tenths of a second).

If you do manage to capture a series of totality exposures, you can turn them into a thing of beauty using a computer. There’s image-processing software that allows you to rotate and align individual frames to match and create seamlessly blended stacks of short, medium, and long exposures to achieve amazing results. The lovely image at the beginning of this article is a composite of 13 telephoto shots with exposures ranging from 1/1,600 to 1/13 second at ISO 640 and f/10.

One thing you do not want to do is spend all of totality looking at the Sun through your camera’s viewfinder and/ or wasting time adjusting your camera’s settings. So here’s a sequence you might consider:

- A minute or so before second contact, adjust your f-stop and shutter speed to be ready for second contact.

- When everyone starts screaming “diamond ring!” take the solar filter off your camera and start shooting. Keep firing until the brilliant diamond is gone, the corona emerges, and you’re enveloped in the darkness of the Moon’s shadow.

- Next, have a quick look around — at the corona, the sky, the horizon, and your fellow eclipse observers.

- Now concentrate on shooting the corona. Run through your exposure sequence from short to long at a fixed f-stop.

- Reset your camera so you’re ready to shoot at third contact.

- Now…look up and enjoy the show! The vast range of coronal brightness, the beautiful detail within the corona, and the delicate shading of the sky down to the colors on the horizon are something only your eye can take in. No matter how good your photographs, they won’t do justice to the real thing. So make sure you take the time to see totality with your own eyes.

- You’ll have a little warning before the arrival of third contact. The edge of the corona opposite where the Sun vanished starts to brighten, red prominences may rise, and an arc of red light (the chromosphere) appears from behind the dark lunar limb. Third contact is imminent — so start shooting. As soon as the diamond ring becomes bright and the corona begins to fade, reattach the solar filter to your camera. Totality is over.

If you’ve never experienced totality before, don’t attempt a complex photographic sequence. If you feel you must try to capture the event, execute steps 1 and 2, then skip straight to step 6. If you remember, start shooting again (step 7) when you see third contact approaching.

Odds and Ends

- Make sure your camera’s flash is turned off. Flashes are an annoyance and, if nothing else, spoil the mood of the spectacle. If you use a point-and-shoot camera, and you’re not sure you can turn the flash off, put a piece of black tape over the flash for extra security.

- Most cameras have optical and digital zooms. Turn off the digital zoom; it’s basically useless.

- Shoot at the highest image-quality setting your camera supports (RAW if possible).

- Use a remote control or cable release to avoid “camera shake.” This is probably an optional extra that didn’t come with your camera, so pick up one (and test it) before eclipse day.

- Bring extra batteries, and insert fresh ones before first contact (that is, before the beginning of the partial eclipse). If you’re using rechargeable batteries, charge them fully before the eclipse begins, and have a spare set, also fully charged, that you can insert shortly before annularity or totality.

- Bring an extra empty, formatted memory card, insert it prior to the start of the eclipse, and then remove it (and lock it, if possible) after the eclipse has ended.

- If you’re in the path of totality for a total solar eclipse bring a flashlight, preferably one that shines with red light. It can get dark enough during totality that you won’t be able to see your camera settings without one!

Videography

Today’s DSLRs, DSLMs, and smartphone cameras offer excellent video quality and reasonable sound — there’s no longer any need to bring a dedicated video camera. During a total solar eclipse, there is much whooping and hollering when totality strikes, and it’s always entertaining to watch and listen to the playback after the event. Indeed, many eclipse veterans will tell you that the best part of any total-solar-eclipse video is the audio! An annular eclipse doesn’t elicit the same wild enthusiasm from eclipse watchers, but a video record of the event will certainly help evoke memories of your adventure.

The same rules that apply to still photography apply to video imagery, especially the one about keeping a proper solar filter attached to your camera if you’re shooting closeups of the Sun. Before the eclipse, use the zoom function to determine the optimum image size of the solar disk (ignore any digital-zoom option), and shoot a short bit of test footage just to make sure your settings are good.

During the partial phases, shoot three- to five-second clips of the Sun every four or five minutes to produce a time-lapse sequence that will compress the multi-hour event into minutes. This is best done with your camera mounted on a tripod. Depending on the image size of the solar disk, you may want to let the video run continuously from just before second contact to just after third to capture Baily’s Beads popping on and off and to show the Moon moving across the solar face in real time (keeping in mind that all this will take several minutes). For a total eclipse, but not an annular eclipse, remember to take the solar filter off at second contact and to replace it at third.

Another option for a total solar eclipse is to set your camera to record a wide-field view of your observing site. If you start recording 10 minutes before the onset of totality, you’ll capture the changing light levels, the approaching or receding lunar shadow (depending on whether the camcorder is aimed west or east, respectively), the horizon glow at totality, and the reactions of people around you. Combined with the audio track, it’ll likely be one of the most engrossing pieces of video you’ll ever shoot.

If you want to share images and videos on social media or post them on blogs, shooting with a smartphone camera is fine. But if you’re concerned about image quality, a DSLR or DSLM is the way to go. If you’re using one, you should determine, in advance, if you want to shoot stills or video, particularly if you plan to capture Baily’s Beads. While the overall eclipse is a leisurely affair, the beads are a rapidly changing event. Decide a few minutes before second and/or third contacts how you want to image them. Do not change your mind at the last minute! Reconfiguring your camera with annularity or totality bearing down on you means you could well end up with no images or video at all.

Want to see some examples? There are vast numbers of solar eclipse videos on YouTube and Vimeo.

Keeping It Simple

What if you don’t have big-time camera gear, or you just want to enjoy the eclipse but still want a photographic memento of the event? Forget everything you just read! Well, not everything (especially not the details about using solar filters), but a lot of it! Here’s why.

Late-model cameras and lenses allow you to do things that weren’t possible before, rendering some of the tried-and-true traditional advice moot. For example, thanks to image stabilization, you can hand-hold a camera with a modest telephoto lens and achieve sharp images without a tripod. And thanks to reasonably noise-free high-ISO performance, you can use ISO settings of 1,600, 3,200, or even higher for faster shutter speeds. During a total solar eclipse, you might be able to capture the middle to outer corona with exposures as short as 1/15 second!

Thanks to sophisticated autofocus capabilities, you can even get away with no manual focus capability. Instead, autofocus on the arc of the partially or annularly eclipsed Sun, or during totality on where the Moon’s silhouette is ringed by the bright corona. However, first you have to tell your camera to autofocus using only the center spot, not the whole array of focus points.

And then there's your smartphone. The cameras on the latest models can produce better results than dedicated point-and-shoot cameras did just a few years ago. New products such as Solar Snap and its included app for your smartphone make easy work of sizing the solar image, focusing, and adjusting the exposure. In addition, you can buy auxiliary lenses that strap on to your phone to enable high-magnification telephoto or superwide-angle shots, adapters that let you connect your smartphone camera to a telescope eyepiece, and apps that give you control over shutter speed, aperture (f-stop), and sensitivity (ISO rating). And, of course, smartphones can capture not only still images, but also video and audio.

Remember to place a solar filter over your phone’s camera lens if you plan to snap pictures of the partially or annularly eclipsed Sun, or over the front of your telescope if you plan to shoot the partial phases or any phase of an annular eclipse with your phone attached to the eyepiece.

The main challenge with using smartphone cameras for astronomical photography is that they tend to overexpose bright objects (e.g., the Moon or the inner solar corona) and have trouble focusing on dim objects (e.g., almost everything else in the sky). Zooming in to make the subject bigger often helps. If your smartphone camera has an HDR (high dynamic range) feature, turn it on and hold your phone very steady — use a tripod if possible. In HDR mode your phone’s camera will automatically take several images in rapid succession with different exposures; with any luck, one of them will be pretty good, or you can combine several to get a composite that’s reasonably well exposed across the entire frame.

Patricia Reiff, science lead at the Rice Space Institute and a veteran eclipse chaser, offers the following recommendation for would-be smartphone eclipse photographers: Choose video mode — not still-image mode — and prop your camera (or use a tripod) so that it faces northwest toward your observing group. Record video (and audio) from a minute or two before annularity or totality begins to a minute or two after it ends. During a total eclipse, if you’re lucky, you’ll capture one of its most dramatic effects: the Moon’s dark shadow racing toward you and washing over you at more than 1,000 miles per hour. Once that happens, look up, and WHAM! there’s the totally eclipsed Sun! Recording the visual and voice reactions of your friends and family throughout totality is priceless. Other eclipse-watchers will take better pictures of the eclipse, but they won’t capture your reaction!

Final Thoughts

A little preparation goes a long way. Always perform at least one dry run with all your gear before eclipse day. This is critical because, depending on your location, you might not be able to pick up forgotten equipment or replace gear that you discover doesn’t work once you start shooting.

However you decide to photograph the upcoming annular and/or total solar eclipse(s), remember to actually look at the eclipse! Don’t spend all your time gazing through your camera’s viewfinder. No image, still or video, can compare with the experience of the real thing.

More Articles About Solar-Eclipse Imaging & Video

- "Smartphone Photography of the Eclipse" (Sten Odenwald, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

- "How to Photograph a Solar Eclipse" (Fred Espenak, MrEclipse.com; includes table of ISO settings, f-stops, and exposures)

- "Photographing the Eclipse! Do You Really Want to Do It?" (Dan McGlaun, Eclipse2024.org)

- "Photographing Solar Eclipses" (Bill Kramer, Eclipse-Chasers.com)

- "Tips for Photographing a Total Solar Eclipse" (Edwin Aguirre & Imelda Joson, Sky & Telescope)

Here's a handy online tool to help you choose your camera settings:

- Shutter Speed Calculator for Solar Eclipses (Xavier Jubier)

Here are some of the most remarkable images ever captured of total solar eclipses:

- Eclipse Photography Home Page (Miloslav Druckmüller)

Our Books & Articles page includes links to several extensive treatments of eclipse imaging:

Our Apps & Software page includes links to programs that can automate your eclipse imaging:

And, in case you missed the links above, here are two sources of solar eclipse videos:

Some of this information is adapted from material provided to its travelers by solar-eclipse-tour operator TravelQuest International.